The night of July 7, 2016, fractured downtown Dallas. Sirens arrived in uneven waves. Police radio traffic overlapped, cut out, then went silent. Officers reported shots fired. Officers down. The perimeter shifted minute by minute. No one knew where the shooter was or how close he remained.

Alexander L. Eastman did. At that moment, he was not acting as a trauma surgeon. He was a sworn lieutenant with the Dallas Police Department, operating inside an unfolding ambush.

Dr. Alexander Eastman had spent years embedded within law enforcement, an uncommon role for a physician. He trained, deployed, and advanced through a system not designed to accommodate medical professionals. That integration placed him near the ambush site as a sniper targeted officers policing a public protest. Five officers were killed. Nine others were wounded. It was the deadliest attack on U.S. law enforcement since September 11.

Care began before the threat was neutralized. Eastman applied tourniquets, directed treatment, and coordinated communication while the shooter remained at large. Entry was restricted by body armor and tactical positioning. Bleeding was severe. Time compressed into seconds. The traditional sequence of securing a scene before providing care was no longer viable. Intervention occurred at the point of injury, amid ongoing danger.

After the shooter was neutralized, Eastman did not disengage. He drove directly to Parkland Memorial Hospital, where the wounded officers were being transported. The shift from police operations to surgical command was immediate and operational, not symbolic. The injuries were the same. The urgency was unchanged. Only the environment differed.

Eastman later received the Dallas Police Department’s Medal of Valor. More consequential, however, was how the night would be cited in professional settings. It was referenced not as a heroic anomaly, but as evidence. The events of July 7 did not redirect his work. They confirmed conclusions he had been reaching for years.

The unanswered question was not whether the approach worked. It was what it meant for a system when survival increasingly depended on placing medical care in the path of danger before that danger had passed.

Early Formation: From Honors Student to Trauma Resident

Eastman’s professional direction was shaped less by a single turning point than by environments that rewarded breadth over narrow specialization. He completed his undergraduate education through the Plan II Honors Program at the University of Texas at Austin in 1996. The program emphasized history, ethics, and systems thinking. Problems were treated as interconnected rather than isolated. That orientation persisted.

Medical school took him to Washington, D.C., at George Washington University, where he earned his M.D. with Distinction in 2001 and was elected to Alpha Omega Alpha. Medicine unfolded alongside policy and federal institutions. Earlier experience as a staff assistant on the U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means reinforced a working understanding of how large systems function under constraint.

He returned to Texas for postgraduate training at UT Southwestern Medical Center and Parkland Memorial Hospital, completing a general surgery residency between 2001 and 2008. Parkland’s trauma service operated at sustained intensity. Gunshot wounds, blunt trauma, and complex injuries arrived continuously. Patterns emerged quickly.

The injuries themselves were familiar. The failures were not. Patients with survivable injuries deteriorated before reaching definitive care. Delays occurred upstream of the operating room. By the time surgery began, physiology had already collapsed. Eastman began to view these outcomes not as clinical inevitabilities, but as structural consequences.

Rather than narrowing his training, he expanded it. Between 2004 and 2006, he completed a fellowship in the Government Emergency Medical Security Services and Homeland Security while receiving an NIH Ruth L. Kirchstein National Research Service Award. In 2009, he completed a fellowship in Trauma and Surgical Critical Care and earned a Master of Public Health. Policy, design, and coordination were formalized as variables on par with technique.

Board certification positioned him for a conventional academic path. Instead, he pursued law enforcement training, obtaining Basic Peace Officer certification in December 2009. The decision reflected where he had seen delays occur. Authority over injury scenes often belonged to systems outside medicine.

Early leadership roles followed. Alongside surgical practice, Eastman assumed medical leadership positions with Dallas Fire Rescue, participating directly in EMS oversight, disaster planning, and interagency exercises. The conclusion was reinforced. Trauma care did not begin at the hospital door. It began wherever injury occurred.

The Innovation: Inventing Tactical Medicine

By the early 2000s, Eastman had reached a conclusion that unsettled both medicine and law enforcement. Trauma surgeons treated gunshot wounds daily, yet were excluded from the environments where those injuries occurred. The separation was intentional. Law enforcement doctrine prioritized control. Medical doctrine prioritized safety and delayed entry. The outcome was predictable. Survivable injuries became fatal while bleeding went untreated.

In 2004, while still a surgical resident, Eastman argued that this division was no longer defensible. His proposal was operational rather than theoretical. Trauma physicians should be embedded within law enforcement tactical units, trained to operate under command, and capable of delivering care during active threats rather than after scene clearance. The goal was not to replace paramedics or hospitals. It was to eliminate delay.

Instead of advocating from the periphery, Eastman integrated fully. He trained as a law enforcement officer, accepted sworn authority, and learned to operate tactically. He joined the Dallas Police Department SWAT program as a participant, not an advisor, and eventually served as the Chief Medical Officer and a commissioned lieutenant. Medical capability became institutional rather than conceptual.

The premise was straightforward. Care must exist where injury risk is highest, even when conditions are unstable. That required physicians to understand movement, communication, and command. It required officers to treat medical intervention as part of operational planning rather than an afterthought.

As the model matured, it reshaped doctrine. Scene safety was no longer treated as a fixed threshold. It became dynamic. Care could occur during movement and containment when teams were trained and coordinated. Early hemorrhage control consistently improved survival. Delay remained the most lethal variable.

The approach drew national attention. Other departments requested guidance. Federal task forces sought input. Professional organizations convened working groups. What began locally became a reference point.

The model was publicly tested during the Dallas ambush. Care occurred before the threat was fully neutralized. Decisions were made without complete information. Loss was not eliminated, but the operational logic was reinforced. Departments that had hesitated revised their assumptions.

Criticism persisted. Ethical boundaries. Scalability. Risk normalization. Eastman acknowledged these concerns without retreating from the premise. Systems designed around certainty would continue to fail under pressure.

National Stage: Hartford Consensus and Stop the Bleed

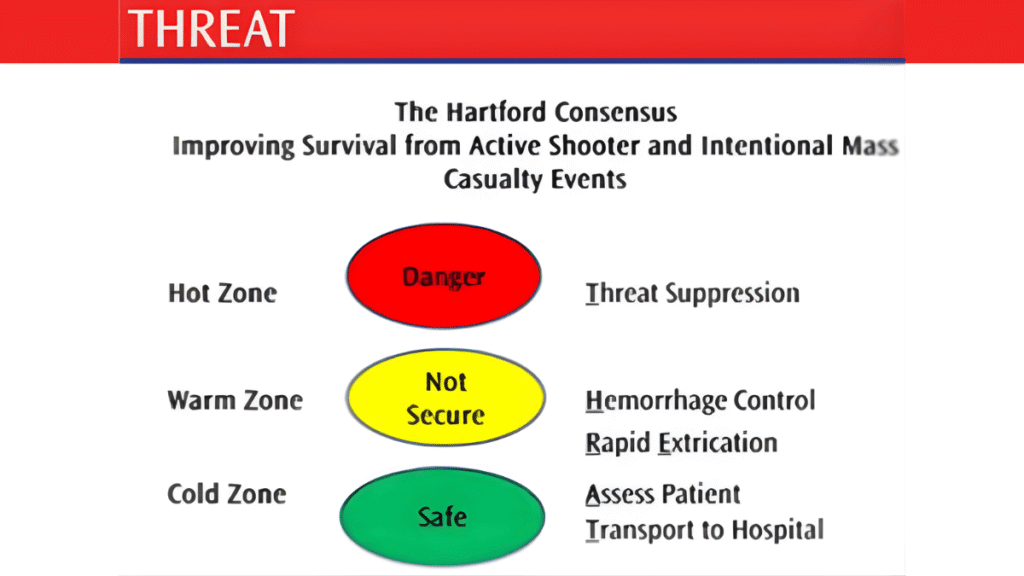

The failures observed in Dallas were not isolated. After the 2012 Sandy Hook shooting, federal officials, surgeons, law enforcement leaders, and emergency physicians convened to examine why casualties continued to die despite advances in medical technology. These meetings became known as the Hartford Consensus.

Eastman participated as a translator between disciplines. The question was not whether trauma centers existed. It was whether systems were designed around how mass casualty events actually unfold. Increasingly, the answer was no.

The Hartford Consensus reframed survival around immediacy rather than credentials. Bleeding could not wait for paramedics. The first person able to act might be a teacher, officer, or bystander. Systems that treated these individuals as passive were structurally misaligned with reality.

This logic informed the THREAT framework, which placed threat suppression and hemorrhage control alongside one another rather than sequentially. Care occurred during stabilization, not after it.

From this framework emerged Stop the Bleed, a civilian preparedness initiative grounded in a single premise. Uncontrolled bleeding is the leading cause of preventable death after trauma. Teaching civilians to control bleeding could save lives.

Opposition followed. Concerns about liability, psychological burden, and normalization of violence surfaced. The initiative did not attempt to resolve those debates. It addressed a narrower reality. People were dying in minutes. Inaction was not neutral.

As Stop the Bleed became embedded into national preparedness, Eastman’s influence became structural rather than visible. Language changed. Training expectations shifted. The definition of a first responder expanded.

Academic and Clinical Leadership in Dallas

While his ideas gained national traction, Eastman’s daily work remained anchored in Dallas. From 2008 to 2018, he held faculty appointments at UT Southwestern and leadership roles at Parkland Memorial Hospital, including Interim Trauma Medical Director and later Chief of the Rees Jones Trauma Center.

As Disaster Medical Director, he oversaw planning for mass casualty incidents and system-wide failures. Planning was informed by repeated exposure to catastrophic injury under compressed timelines.

Hospital leadership reinforced a consistent priority. Trauma centers could not function as isolated endpoints. Their effectiveness depended on integration with EMS and law enforcement. Administrative decisions were evaluated by whether they reduced friction between systems.

Teaching remained central. Trainees were taught to anticipate failure points, communicate under pressure, and make decisions with incomplete information. Disaster response and systems thinking were treated as core competencies.

By 2018, the scope of his work exceeded what a single institution could contain. He transitioned away from full-time academic leadership to expand federal involvement. The Dallas years marked the shift from concept to infrastructure.

Transition to Federal Service

By the mid-2010s, Eastman’s work scaled beyond any single city. In 2016, he entered federal service with the Department of Homeland Security, moving from operational integration to system-wide design.

Roles within the Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office and later the Office of Health Security placed medical readiness alongside intelligence, enforcement, and emergency management. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these assumptions were tested at scale. Operations continued under conditions where exposure was unavoidable.

In 2023, Eastman was appointed Acting Chief Medical Officer for U.S. Customs and Border Protection, overseeing health services in one of the most complex operational environments in government. Health issues affecting migrants were operational realities, not abstractions.

Federal service amplified ethical tension rather than resolving it. Decisions carried population-level consequences. Outcomes were measured in system performance under pressure.

Research, Publications, and Teaching Legacy

Eastman’s academic work emerged directly from operational experience. He authored or co-authored more than 79 peer-reviewed publications examining where care fails under stress. Delay was treated as a measurable variable, not an abstraction.

He co-edited the Parkland Trauma Handbook and contributed to major texts on trauma surgery and disaster response, consistently emphasizing care outside traditional hospital settings.

Teaching focused on decision-making under uncertainty. Leadership, preparedness, and system design replaced procedural mastery as central themes.

Scholarship, training, and operations formed a continuous loop. Each informed the next. The measure was a consequence.

A Career at the Intersection

When Systems Collide

Dr. Alexander Eastman’s career does not resolve into a single professional identity, nor does it lend itself to a clean conclusion. It unfolds instead across overlapping systems that were never designed to share authority as closely as they now must. Medicine. Law enforcement. Public health. National security. Each carries its own logic. Each responds differently under pressure. Eastman’s work has existed where those logics collide.

What distinguishes his trajectory is not boundary crossing for its own sake, but sustained exposure to failure and a refusal to treat it as inevitable. Again and again, catastrophic injury revealed the same pattern. Harm occurred quickly. Delay followed. Delay exposed design flaws that had existed long before crisis arrived.

This work has never been free of tension. Embedding medical leadership within law enforcement raises unresolved questions about neutrality and risk. Federal medical authority inside security agencies carries political and ethical weight. Teaching civilians to control bleeding asks ordinary people to assume responsibilities once reserved for professionals. Eastman has not attempted to resolve these tensions rhetorically. He has operated within them, treating ambiguity as a condition rather than an obstacle.

Ethics Without Certainty

Work at the intersection of medicine and public safety carries ethical weight that cannot be resolved by protocol alone. Trauma surgery and law enforcement operate under different moral frameworks, yet they increasingly converge in moments defined by catastrophic injury and irreversible consequence. For clinicians who move between these domains, ethical clarity is not assumed. It must be actively maintained.

In trauma surgery, the obligation is clear in principle. Preserve life. Minimize harm. Act in the patient’s best interest, often with limited information and extreme time pressure. Public safety environments complicate that clarity. Decisions unfold amid active threats, legal authority, and competing responsibilities to officers, bystanders, and broader operational goals. When those priorities overlap, ethical alignment is not guaranteed.

One recurring tension involves proximity to danger. Medical ethics traditionally emphasize neutrality and personal safety. Public safety work assumes calculated risk as a condition of service. When physicians operate within tactical or law enforcement settings, the ethical question is not whether risk exists, but who may assume it, and under what justification. The answer cannot be abstract. It depends on context, preparation, and consequence.

Role clarity presents another challenge. A clinician operating inside security environments may simultaneously hold medical authority and operational responsibility. That dual status complicates consent, confidentiality, and decision-making. Actions taken to preserve life may also advance enforcement objectives, even when that is not the intent. Ethical practice in such settings relies less on fixed rules than on continuous self-examination.

Catastrophic injury compresses these dilemmas further. When outcomes hinge on seconds, ethical deliberation becomes immediate and incomplete. Decisions are made before reflection is possible. The moral residue of those moments does not dissipate once the event ends. Over time, repeated exposure to severe injury and loss tests not only ethical consistency, but also personal endurance.

There is also the risk of normalization. As medical practice adapts to environments shaped by violence and disaster, preparedness can begin to resemble acceptance. Training civilians in hemorrhage control and embedding physicians within security operations are pragmatic responses, but they carry an implicit acknowledgment that catastrophic injury is no longer exceptional. Navigating that reality without surrendering to fatalism remains an unresolved ethical task.

What emerges is not a single ethical framework, but an ongoing practice of negotiation. Principles remain intact, but their application must adapt to environments where delay costs lives and certainty is rare. Ethical practice in these spaces is defined less by perfect answers than by sustained integrity under pressure.

Delay as Design

The ambush in downtown Dallas in 2016 did more than reveal individual vulnerability. It tested the durability of an entire trauma system under real-world conditions. The response unfolded across streets, vehicles, and hospital corridors, exposing how tightly outcomes were bound to preparation, coordination, and institutional design rather than individual action alone.

At Parkland Memorial Hospital, the arrival of patients with catastrophic injuries forced trauma protocols into their most compressed form. Surgeons, nurses, and support staff operated within minutes, not margins. What mattered was not improvisation, but whether systems built over years could absorb shock without fracturing. Parkland’s role as a regional trauma hub meant that decisions made long before that night shaped what was possible during it.

Those systems were inseparable from surgical training at UT Southwestern Medical Center, where trauma education emphasized volume, repetition, and exposure to worst-case scenarios. The training pipeline produced clinicians accustomed to rapid decision-making under constraint. Yet the ambush underscored a persistent reality. Even the strongest hospital response begins too late if earlier links fail.

The event exposed the importance of infrastructure beyond hospital walls. Communication between law enforcement, emergency medical services, and trauma centers determined how quickly injured patients moved through the system. Each handoff carried risk. Each delay compounded the next.

What emerged was not a story of institutional success or failure in isolation, but of interdependence. A trauma system functions only as well as its weakest link. Catastrophic injury revealed not a medical failure alone, but a systems failure shaped by planning, training, and the willingness to integrate care across environments once treated as separate.

Trauma does not respect institutional boundaries. Systems that insist on them are the ones most likely to fail under pressure.

Before the Next Crisis

In recent years, Dr. Alexander Eastman’s role has shifted further from the point of injury and closer to the architecture that determines outcomes before a crisis occurs. Advisory positions, academic appointments, and federal leadership have replaced regular clinical presence. The work has become quieter, more structural, and less visible. Its success is measured not by recognition, but by absence. Fewer preventable deaths. Fewer failures were attributed to the delay.

The systems influenced by this work remain unfinished. Violence persists. Disasters grow more complex. Institutions remain vulnerable to fragmentation under stress. Eastman’s career does not suggest otherwise. It offers no promise of resolution, only evidence that outcomes change when care is positioned deliberately rather than defensively.

Seen this way, his career functions less as a model to replicate than as a record of adaptation under sustained pressure. It documents how emergency response in the United States has evolved when traditional separations proved inadequate, and how individuals inside institutions can influence that evolution by insisting on proximity, integration, and accountability.

The question is no longer whether medicine belongs closer to danger. Circumstance has already answered that. The unresolved question is how deliberately systems are designed before the next moment when delay becomes the difference between survival and loss.

Waiting for certainty is itself a decision. Often, it is the most consequential one.